Video Sources 0 Views Report Error

Synopsis

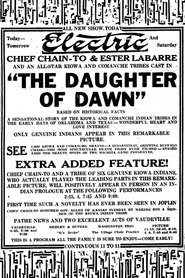

Watch: The Daughter of Dawn 1920 123movies, Full Movie Online – This restored silent film features a love triangle involving a Kiowa chief’s daughter and ensuing conflict between Kiowa and Comanche villages..

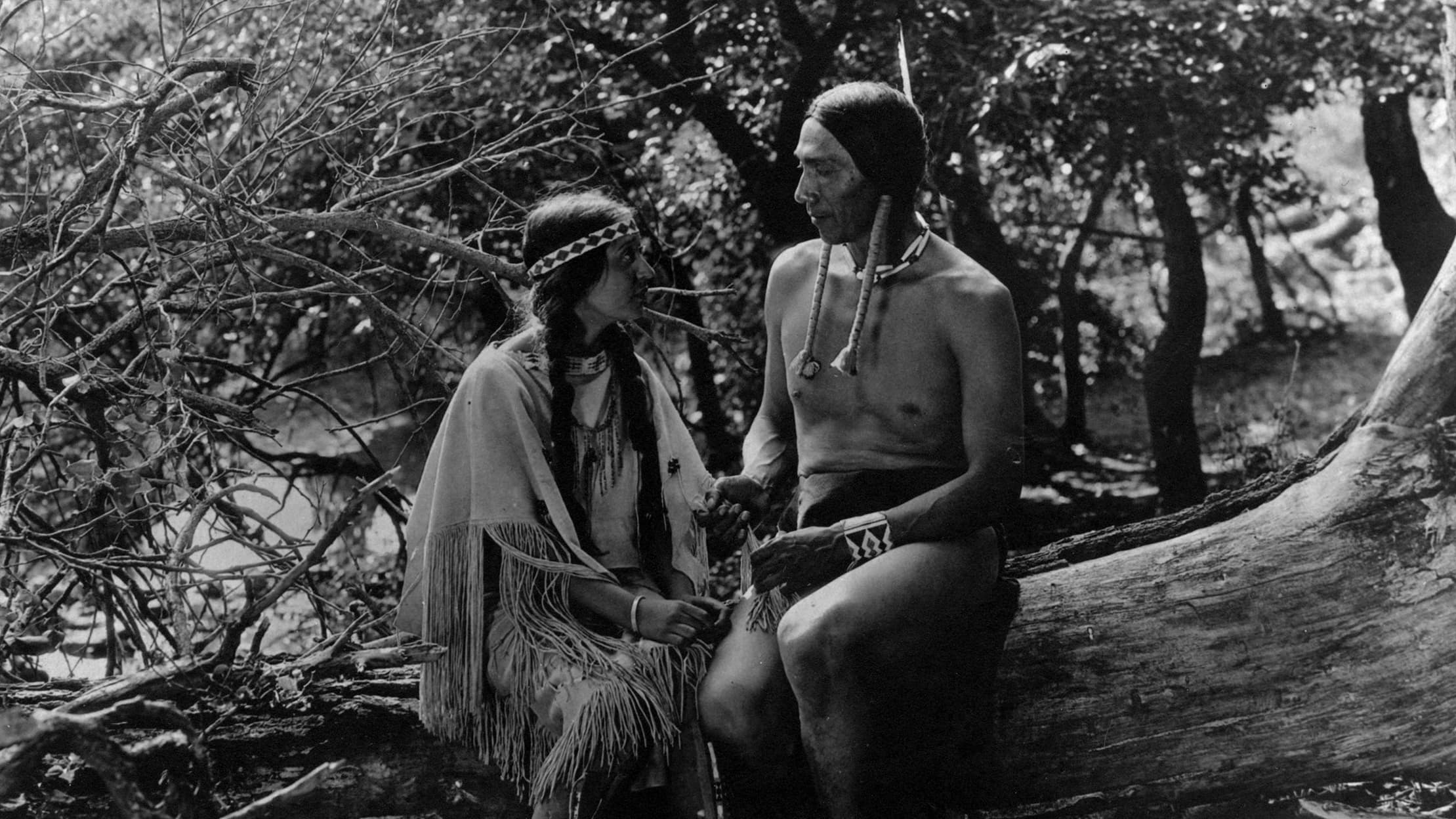

Plot: The Daughter of Dawn is a silent Western, and one of the few films of the silent era to have an entirely Native American cast. It tells the story of a Kiowa woman and her lover, his feats of bravery, and their trials at the hands of a jealous rival and Comanche warriors. Completed in 1920, it was only shown a few times before being considered lost. Five reels of the movie were found in 2005, and restored by the Oklahoma Historical Society in 2012.

Smart Tags: #national_film_registry #native_american #indian #kiowa #comanche #romantic_triangle #father_daughter_relationship #indian_chief #stabbed_in_the_chest #hand_to_hand_combat #suicide #abduction #buffalo #buffalo_hunt #canoe #tipi #cast_out #revenge #native_cast_only #indian_village #raid

Find Alternative – The Daughter of Dawn 1920, Streaming Links:

123movies | FMmovies | Putlocker | GoMovies | SolarMovie | Soap2day

Ratings:

Reviews:

The Look of Native Americans

“Daughter of the Dawn” has become an interesting historical artifact of a 1920 silent film, long considered lost and restored in 2012, including for a home-video release. Much of what would’ve made it a curiosity in 1920 remains the same today, as a view into Native-American culture as portrayed exclusively by Native Americans. While the white men behind the camera, as well as the perhaps the similar makeup of the intended audience for the film, offers a perspective of the exotic and a romanticizing of a racial “other,” the “noble savage” myth, cowboys-and-Indians fighting minus the cowboys, and a stealing-women plot that’s just as at home in “The Searchers” (1956) included, this view is partly subverted by the looks and representation on screen. It’s members of the Kiowa and Comanche, although the Comanche oddly remain “othered,” representing themselves, including reportedly wearing their own clothes and bringing the tepees to the production–offering a semblance of authenticity to the proceedings and determining to a degree how they would be gazed upon. Even the body language and signaling is a marked contrast to the sort of gesticulation as an extension of intertitles usually seen in silent films. Moreover, “The Daughter of Dawn” is cinematographically based on looks, full of masked views and point-of-views shots, sharing the camera’s, and thus our, the spectator’s, perspective through the eyes of the Native Americans.This may be as simple as a character spotting a herd of bison or the lovely forested and hilled spots of Oklahoma Indian Territory. But, the spying on the rival tribe and the creepy shadowing of the love triangle are also based on looks–characters looking and being looked upon, and, indeed, here that mostly means the traditional active male gaze and the female to-be-looked-at-ness. The story is admittedly lackluster and threatens to veer into overwrought melodrama (and doing just that with the character of Red Wing), built as it is on a love triangle that’s resolved by White Eagle and Black Wolf (one can tell just by the color in their names which is supposed to be the baddie) being told to literally jump off a cliff and the subsequent wrestling match of supposed tribal warfare. The underlying cause of these struggles, though, is sexual reproduction. Black Wolf points out to the Comanche that they have few young women in their tribe. Their race is dying. The bison hunt plays into this, too, as it’s said that the Kiowa face starvation without it.

Furthermore, all of this looking is conspicuous for what it doesn’t see. The genocide, forced relocation and cultural marginalization that’s the unspoken raison d’être of the picture. There are no white settlers in the film, but they’re nonetheless like an unspoken, unseen spectre looming outside the frame–why “The Daughter of Dawn” is a fictionalization of a largely lost culture, constantly pushed onto harsher and less-productive landscapes, the numbers of their tribes being depleted. The cinematographic apparatus here becomes part of that invasion, a means to capture this culture and relocate it to distant screens. When films were treated as disposable goods, only of temporary market worth, even the film was nearly lost. The term “lost” doesn’t fully grapple with the destruction wrought, either. They weren’t merely misplaced, never to be found again; they were marginalized, mistreated and willfully destroyed.

Some of the few films that do remain, such as “The Daughter of Dawn,” which others have mentioned alongside a few other such pictures of the time that feature all-native casts, in addition to even some of the Bison Westerns of Thomas H. Ince’s studio, demonstrate that the racist caricatures of Indians in classical Hollywood Westerns promoting Manifest Destiny wasn’t always the case. Even in the silent era, there were more sympathetic portrayals and some attempts at greater screen representation. It’s fortunate that “The Daughter of Dawn” exists and may be seen instead of romanticized. It’s a flawed picture, but a valuable one that deserves to exist and be seen.

Review By: Cineanalyst

The Look of Native Americans

“Daughter of the Dawn” has become an interesting historical artifact of a 1920 silent film, long considered lost and restored in 2012, including for a home-video release. Much of what would’ve made it a curiosity in 1920 remains the same today, as a view into Native-American culture as portrayed exclusively by Native Americans. While the white men behind the camera, as well as the perhaps the similar makeup of the intended audience for the film, offers a perspective of the exotic and a romanticizing of a racial “other,” the “noble savage” myth, cowboys-and-Indians fighting minus the cowboys, and a stealing-women plot that’s just as at home in “The Searchers” (1956) included, this view is partly subverted by the looks and representation on screen. It’s members of the Kiowa and Comanche, although the Comanche oddly remain “othered,” representing themselves, including reportedly wearing their own clothes and bringing the tepees to the production–offering a semblance of authenticity to the proceedings and determining to a degree how they would be gazed upon. Even the body language and signaling is a marked contrast to the sort of gesticulation as an extension of intertitles usually seen in silent films. Moreover, “The Daughter of Dawn” is cinematographically based on looks, full of masked views and point-of-views shots, sharing the camera’s, and thus our, the spectator’s, perspective through the eyes of the Native Americans.This may be as simple as a character spotting a herd of bison or the lovely forested and hilled spots of Oklahoma Indian Territory. But, the spying on the rival tribe and the creepy shadowing of the love triangle are also based on looks–characters looking and being looked upon, and, indeed, here that mostly means the traditional active male gaze and the female to-be-looked-at-ness. The story is admittedly lackluster and threatens to veer into overwrought melodrama (and doing just that with the character of Red Wing), built as it is on a love triangle that’s resolved by White Eagle and Black Wolf (one can tell just by the color in their names which is supposed to be the baddie) being told to literally jump off a cliff and the subsequent wrestling match of supposed tribal warfare. The underlying cause of these struggles, though, is sexual reproduction. Black Wolf points out to the Comanche that they have few young women in their tribe. Their race is dying. The bison hunt plays into this, too, as it’s said that the Kiowa face starvation without it.

Furthermore, all of this looking is conspicuous for what it doesn’t see. The genocide, forced relocation and cultural marginalization that’s the unspoken raison d’être of the picture. There are no white settlers in the film, but they’re nonetheless like an unspoken, unseen spectre looming outside the frame–why “The Daughter of Dawn” is a fictionalization of a largely lost culture, constantly pushed onto harsher and less-productive landscapes, the numbers of their tribes being depleted. The cinematographic apparatus here becomes part of that invasion, a means to capture this culture and relocate it to distant screens. When films were treated as disposable goods, only of temporary market worth, even the film was nearly lost. The term “lost” doesn’t fully grapple with the destruction wrought, either. They weren’t merely misplaced, never to be found again; they were marginalized, mistreated and willfully destroyed.

Some of the few films that do remain, such as “The Daughter of Dawn,” which others have mentioned alongside a few other such pictures of the time that feature all-native casts, in addition to even some of the Bison Westerns of Thomas H. Ince’s studio, demonstrate that the racist caricatures of Indians in classical Hollywood Westerns promoting Manifest Destiny wasn’t always the case. Even in the silent era, there were more sympathetic portrayals and some attempts at greater screen representation. It’s fortunate that “The Daughter of Dawn” exists and may be seen instead of romanticized. It’s a flawed picture, but a valuable one that deserves to exist and be seen.

Review By: Cineanalyst

Other Information:

Original Title The Daughter of Dawn

Release Date 1920-10-10

Release Year 1920

Original Language en

Runtime 1 hr 20 min (80 min)

Budget 0

Revenue 0

Status Released

Rated TV-G

Genre Romance, Western

Director Norbert A. Myles

Writer Norbert A. Myles, Charles Simone, Richard Banks

Actors White Parker, Esther LeBarre, Hunting Horse

Country United States

Awards 1 win

Production Company N/A

Website N/A

Technical Information:

Sound Mix Silent

Aspect Ratio 1.33 : 1

Camera N/A

Laboratory N/A

Film Length N/A

Negative Format 35 mm

Cinematographic Process Spherical

Printed Film Format 35 mm

Original title The Daughter of Dawn

TMDb Rating 4.9 19 votes